A note about notes

Why I write so much, and how Obsidian helps me unlock the true power of notes

You just finished a book you simply couldn’t put down before finishing. Maybe it was the novel way of thinking about a problem, or the beautiful language, or some worldview-shattering research - either way, you were hooked. Fast-forward 6 months later, you’re recommending the game-changing book to a friend, and they ask some probing questions to understand what made it so special.

You’re stuck - what was the core argument premised on again? And what about that chapter distilling a key area of the literature? Fast-forward 4 years later, you only remembered that you’ve even read the book because you dug it out of a moving box. Or were you going to read it?

Over the course of the ~2.5 years, I’ve been reading around the topic of personal knowledge management (PKM) and related areas like note-taking and metacognition. In trying to adopt better ways to understand how I collect, digest, organise, and combine things I learn (aka PKM), I have also gotten more serious about the tools I use, and have been trying out a few different ones.

Somewhat ironically, I wrote most of this post back in early 2021, and then redrafted it a few times, but was never happy with it. In the spirit of writing/posting more often, rather than trying to be a perfectionist and posting never, I’ve tidied my most recent draft and posted it as-is. I might come back to this and re-write it at some point in the future, digital garden-style.

Brains suck (at least mine does)

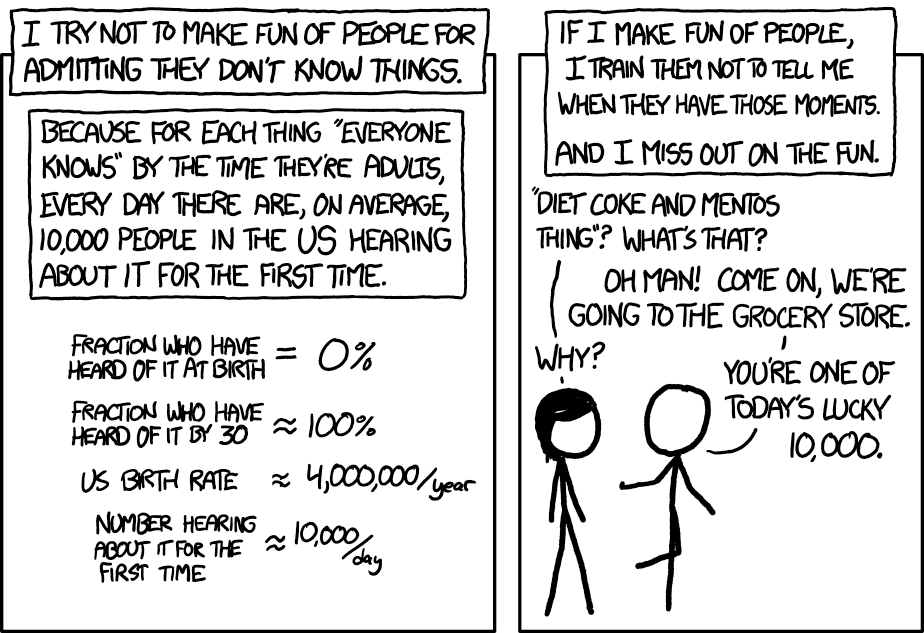

The brain sucks at many things. Wikipedia had over 200 different cognitive biases at the time I wrote this paragraph. For this piece, I am mostly referring to the 50 or so that relate to memory, like the Google effect, which is the tendency for people to forget things that are easy to Google. In short? Human memory sucks - and mine doubly so. Maybe it’s because I’m quite good at Googling? (By which I mostly mean I can’t help but rely on it, though I do think it’s a skill - maybe I’ll write about that another day)

We all come across powerful ideas, insightful comments, and interesting facts all the time, from all angles. Books, articles, podcasts, tweets, conversations - each has something to offer. And over time, as all this knowledge accumulates, we grow wiser and better-able to connect it all together, even if it’s been years in between each different piece! Or do we?

Echoing Tiago Forte:

We feel a constant pressure to be learning, improving ourselves, and making progress. We spend countless hours every year reading, listening, and watching informational content. And yet, where has all that valuable knowledge gone? Where is it when we need it? Our brain can only store a few thoughts at any one time.

In short, it’s hard to remember what we learn, especially when it’s so scattered across different domains and formats. A 15-minute YouTube explainer, a chapter in a book, a conversation with a friend… And when it’s hard to remember, it’s even harder to synthesise different learnings by drawing connections between them (and to then remember those syntheses!). And when you can’t effectively recall those things, it’s harder to bring it up with others, or with your future self.

To sum up, there are four challenges:

- Remembering things

- Clarifying your thinking

- Drawing connections from the different things you learn

- Sharing what you learn with others, or with your future self

Writing, and note-taking specifically, can act as a scaffold for our broken brains

“Notes on paper, or on a computer screen […] do not make contemporary physics or other kinds of intellectual endeavour easier, they make it possible.” — Neil Levy in Handbook of Neuroethics (2011)

Reading without taking notes ⛲️ pic.twitter.com/ViCLEygQKf

— Anne-Laure Le Cunff (@anthilemoon) May 17, 2020

There’s a couple of different ideas that fall under this - each linking back to the 4 challenges listed earlier.

Writing helps us remember. Pretty obvious, but let me call out the two different ways by which this happens:

- The obvious part: Note-taking creates a permanent(ish) retrievable record. Especially in the case of electronic notes, it’s really easy to find and reference a note of something you heard, saw, discussed, or thought about in the past (like this note which I largely wrote 2 years ago, which in turn was a transcript of sorts of many conversations I’d had with folks in 2020 and 2021)

- The part you subconsciously knew about, but maybe weren’t clear on the science behind it: The very act of taking notes helps us form new neural pathways, because we process the information on a deeper level than if we were just passively listening/reading.

By writing, we clarify our own thinking. How many times did you think you had a coherent position on something, and as you started writing it down realised there’s a contradiction, or a missing step, or perhaps even a different conclusion to be drawn?

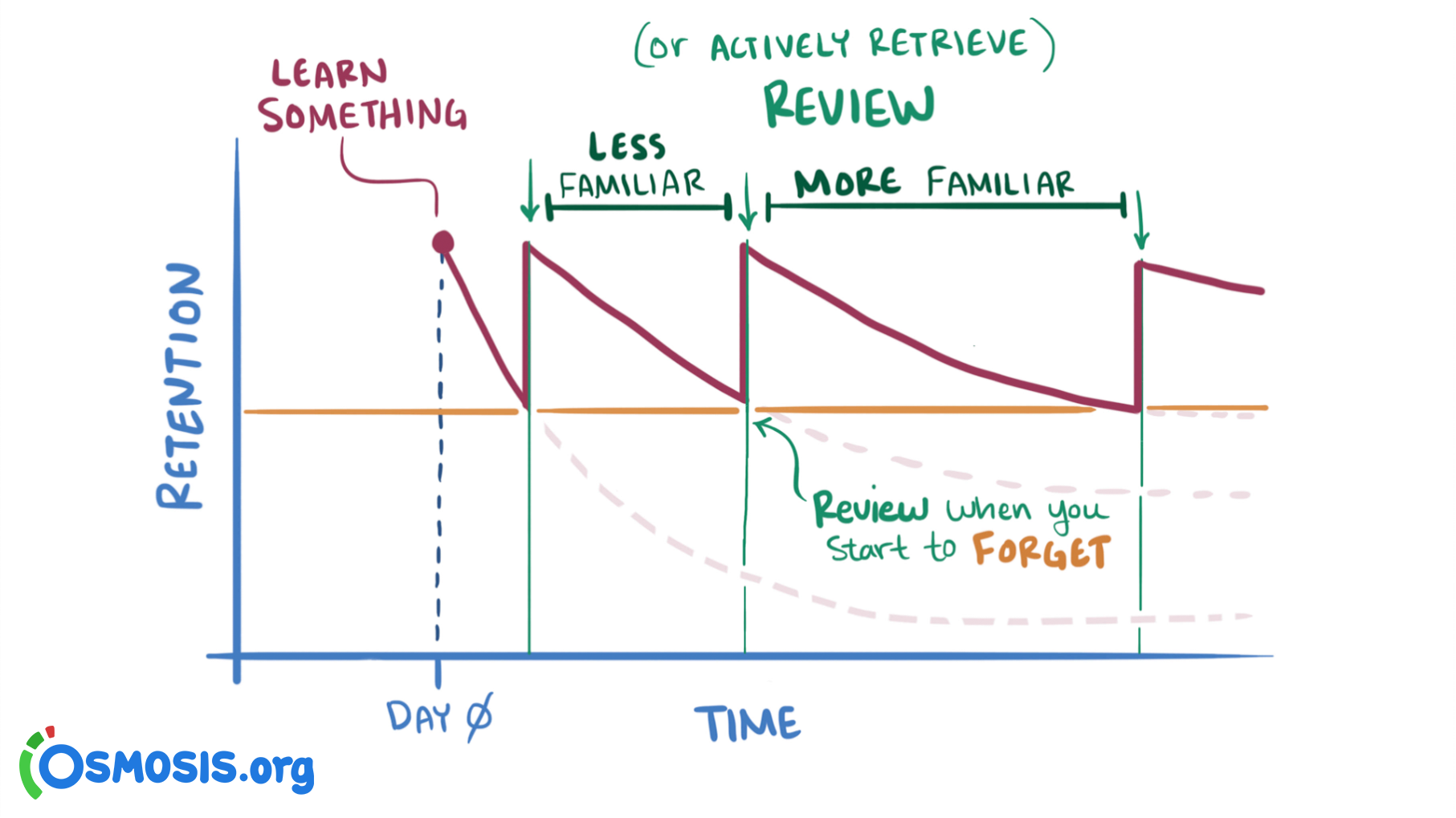

By reviewing our notes periodically, we can make new connections between thoughts and ideas that would otherwise stay siloed in different parts of our brain. This is less about the inherent benefit of note-taking, and more about developing a good system around our notes. I’ve really enjoyed reading Tiago Forte’s Building A Second Brain for this. (on my to-do list: type up all my notes from reading BASB and publish them here!)

One thing I’ve been getting more and more convinced is that my writing and note-taking should not stop with me, and that I should instead by sharing more with the world. This is why I set up this blog, and why I’ve been posting more and more about Data Product Management on LinkedIn and my newsletter. There’s a few different reasons (I quite like this article about the “three strikes rule” on this) , but broadly I’d summarise them as:

Educating others. You might think something is obvious, or that there’s better sources to learn about that thing from, and while both those things are true, the conclusion isn’t: At the end of the day, there’s simply too many things to know about in the world, and we’re all effectively information channels through which some % of the world’s information moves around. For me, some days that information is cat videos and finance memes, other days it’s product management best practices, and others it’s my third rewatch of The Mandalorian.

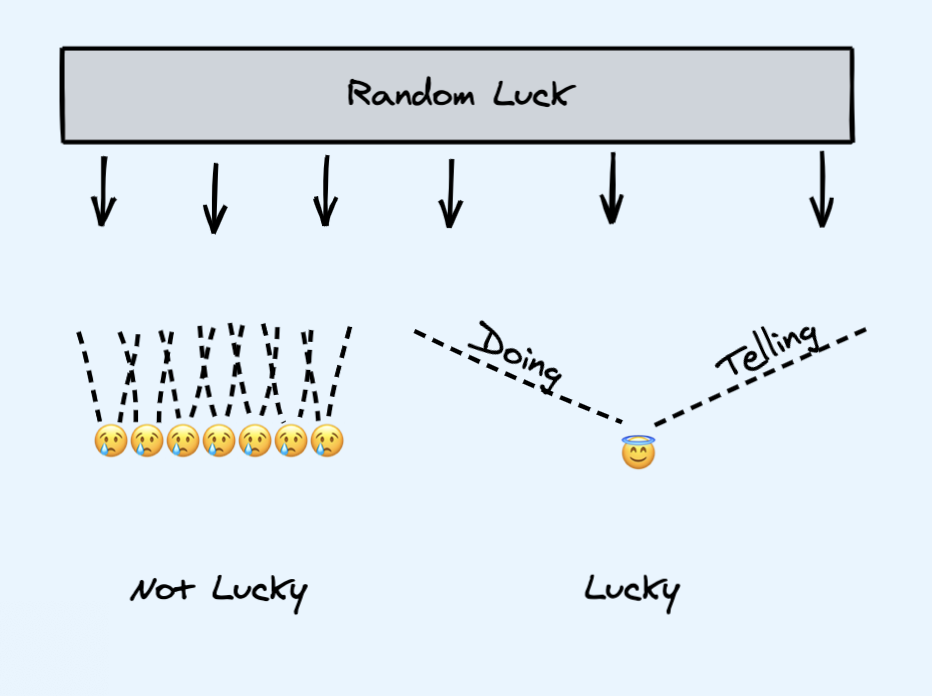

Increasing your luck surface area by making it easier for others to come across you and your ideas. You can think of this from a very career-oriented sigma grindset angle (e.g. “if I make content about my work then prospective employers will get in touch with me”), but it can be just as true for much more day-to-day personal, non-work-related stuff (e.g. “hey I saw from your insta stories that you’re also visiting Barcelona this week, let’s meet up!")

Getting feedback on your ideas and writing. Chances are, both have issues. You could obsess over them on your own to improve, but realistically that is (a) a recipe for crippling self-doubt, but also (b) you’re likely to be riddled with blind spots that you’ll never detect and correct for.

- Most people suck at writing. You can almost always be more consise, or more engaging, or better at structuring your ideas. It takes practice and feedback. Maybe Grammarly and ChatGPT-based writing tools will eventually overtake friends or editors on this (and maybe I should start using the latter more…), but I don’t think we’re there yet.

- If ChatGPT or Autocorrect can’t always improve your writing, it definitely won’t be able to improve the actual ideas you are expressing through it. Putting your thoughts out there for the world to criticise can be scary, but

Taking notes is necessary, but not sufficient

Alright, so I’ve made the abbreviated (but still fairly long) case for why you should take more notes, and write and publish your writing more generally. Time to go back to what this note was originally meant to be about, which is note-taking apps, and why I love Obsidian.

I alluded to this in the last section as well: Taking notes is part of the story, but not everything. Besides sharing what you write and improving through feedback and an open exchange of ideas, I’ve come to realise it’s quite important to use the right tool and process.

Just to be clear, I’m not claiming there is a Single Correct Way To Write Notes. I wanted to elaborate on the criteria I used to pick my writing tool.

These are:

- Eliminating siloes when it comes to my notes/knowledge

- Minimising friction to accessing new and existing notes

- Not being locked into an app that may not exist (or may not be as good) a few years from now

Information siloes part 1: Folders suck

The way I organised my notes until ~2020 did not work for me, but I hadn’t quite accepted it. I used folders, so my notes had a hierarchical structure like Undegrad -> 2nd year -> Political Economy module. All my notes about that module were in that folder, where I also saved lecture slides, essays, and other resources.

The problem with a hierarchical approach is that it is very rigid, and doesn’t reflect how information is captured and stored in our brains.

Say lesson #5 of 2nd year political economy was about Chinese economic growth, a topic I also touched in my third-year political economy module on East Asian economic development, as well as the research I did to prepare for debating tournaments, and that comes up in my personal reading relating to climate change. In a hierarchical paradigm, I would need to go back every time (if I even remember that I did a lecture on the topic 1/2/5/10 years ago…), extract any relevant information, and do whatever it is I was trying to do with it.

It sort of works when we’re talking about two political economy modules taken as part of the same degree, but as the context changes (e.g. uni vs. hobby vs. work project), it becomes much harder for my poor brain to handle. Not only that, but the dimension of time has a compounding effect: Maybe if I was doing all this around the same time it wouldn’t matter, but when we’re talking about years or even decades in between learning or thinking about something, it’s far from trivial.

The end result: I took notes, they were useful in the moment, but longer-term, it’s almost as if I never learned the stuff. At best, I know that the topic exists, so that if I want to re-learn about it I can browse through my notes and probably the source textbooks too.

Nick Milo puts it beautifully in this harrowing line:

It matters how you set up your digital library so it can grow with you, not just this month, or this year, but throughout your life. That’s a really powerful thing, because if you can’t trust your digital notes you’re one step away from digital dementia

Information siloes part 2: Stop using so many apps/mediums

To an extent, this was a self-inflicted problem. There have been periods in my life where I was using

- Apple Notes on my iPhone (which I could also read from my Macbook)

- Google Keep for quick notes on my Macbook

- Google Docs for lecture notes and collab documents

- Microsoft Word for essays

- Loose paper notes for lectures and seminars

- Notepad for other lecture notes and seminars

- Evernote for some essays and debate notes

Looking back, I wonder: Was I insane?

Maybe I was, but I remember why I did it: I was unsatisfied with the tools I was using, and was experimenting with new ones. Sometimes there were practical considerations as well, like I needed Word to do proper referencing, I had to move away from Apple Notes when I got a Windows computer, but most of the time it was more of a case of “for this project I’ll use this app, but I cba to move everything else on here”.

One of the biggest advantages of digital notes (which in some ways are inferior to paper ones, like for example in how effective they are at crystalising what we learn while writing them) is Ctrl+F. But when you have your notes scattered across different apps and formats, you massively diminish the retrievability of your information. In some cases you can still do it (e.g. Word docs + Google Docs stored in Google Drive can both be search by Google Drive), but in others you can’t (Windows or Google can’t index Evernote or Notion notes).

So, I needed to (a) find a tool that I can use across my devices, and also (b) actually stick to one instead of flip-flopping around.

There needs to be almost no friction to writing a new note

When I get an idea, I need to be able to get it down in writing ASAP. Sometimes even 10 seconds is enough for me to lose my train of thought, which is why I always carry around my phone (and usually my A5 notebook as well). When I work, I either have my notes app open, or my notepad, or both. For example when I’m sharing my screen, I need to be able to still write things down.

Recently, I’ve also started using Otter to record and transcribe voice notes, for when I get a thought on the move (I’ve also found I can draft ideas more effectively if I talk through them first, even if it’s just to myself).

There should also be minimal friction in finding a note I’m looking for

Same principle as above. If it takes ages to find the right note, realistically that means I will often not bother, or not have time (and e.g. I’ll create a new note about the same topic, because I was in a hurry). So it’s important to have tools like powerful search functionality, tagging, and metadata to help me find what I’m after.

Bonus points if there are ways to surface notes from time to time that I’m not even actively looking for. Spaced repetition is key for learning and remembering things, after all.

My notes need to be portable

There’s a lot of really cool tools for writing out there. The newer ones blend best-in-class UX design with powerful features like Generative AI, linked nodes, and databases. From the more “basic” (yet still super powerful) modern note-taking apps like Notion, to some of the more exciting newer players like Roam Research, Mem and Tana, we’re really seeing an explosion in teams building awesome products to help individuals and teams think, write, and work better. These recognise that the distinction between “note”, “task”, and “database” are much more artificial than software companies would have us think when they try to sell us one app for notes, another for docs, another for spreadsheets, and another for to-dos (and another for team to-dos)1.

But will they last? A lot of these are VC-funded apps that have sought rapid growth before figuring out details like profitability. Even if they’re profitable, some are bound to be acquired by bigger players looking to offer a more complete product bundle (and/or kill off threats to their shittier-but-enormously-profitable cash cow products2).

Maybe they’ll last, but something better will come. Tana, for example, is one of the newest kids in the block, and it combines a lot of the best of Notion and Roam Research. I’ve started testing it out, but the lack of true portability worries me a lot.

How I use Obsidian, an open-source notes editor, to tackle these challenges

Here’s a quick summary of Obsidian with reference to the challenges listed above:

| Challenge | How Obsidian helps me tackle it |

|---|---|

| Eliminating note siloes when it comes to my notes/knowledge | Obsidian treats all notes as nodes in an interconnected network. You can still use folders, but they are both optional and not the optimal way to use the tool. |

| Eliminating app siloes by using one app instead of many | I still sometimes do stuff in Apple Notes or paper, but it’s more like a workflow now. Apple Notes or paper = rough note I couldn’t put easily on Obsidian for some reason, it needs to be migrated to the right Obsidian note(s). The one silo I definitely maintain is between my personal Obsidian vault and the one I use for my work notes. For non-sensitive topics, like learning about data tools, I try and duplicate what I have (usually that means copy stuff from personal to work), but obviously other notes need to stay firewalled. |

| Minimising friction to accessing new and existing notes | Obsidian works offline, is very lightweight, has powerful search functionality, and offers features like Daily Notes to make it even faster to start writing without having to overthink the admin side of things. |

| Not being locked into an app that may not exist (or may not be as good) a few years from now | Every note is a markdown document, an open file format that can be read by any app on any OS. Even if the company dies, all my notes are mine, I don’t need to rely on something like an “export” functionality (that apps like Notion have an incentive to make cumbersome and unhelpful). |

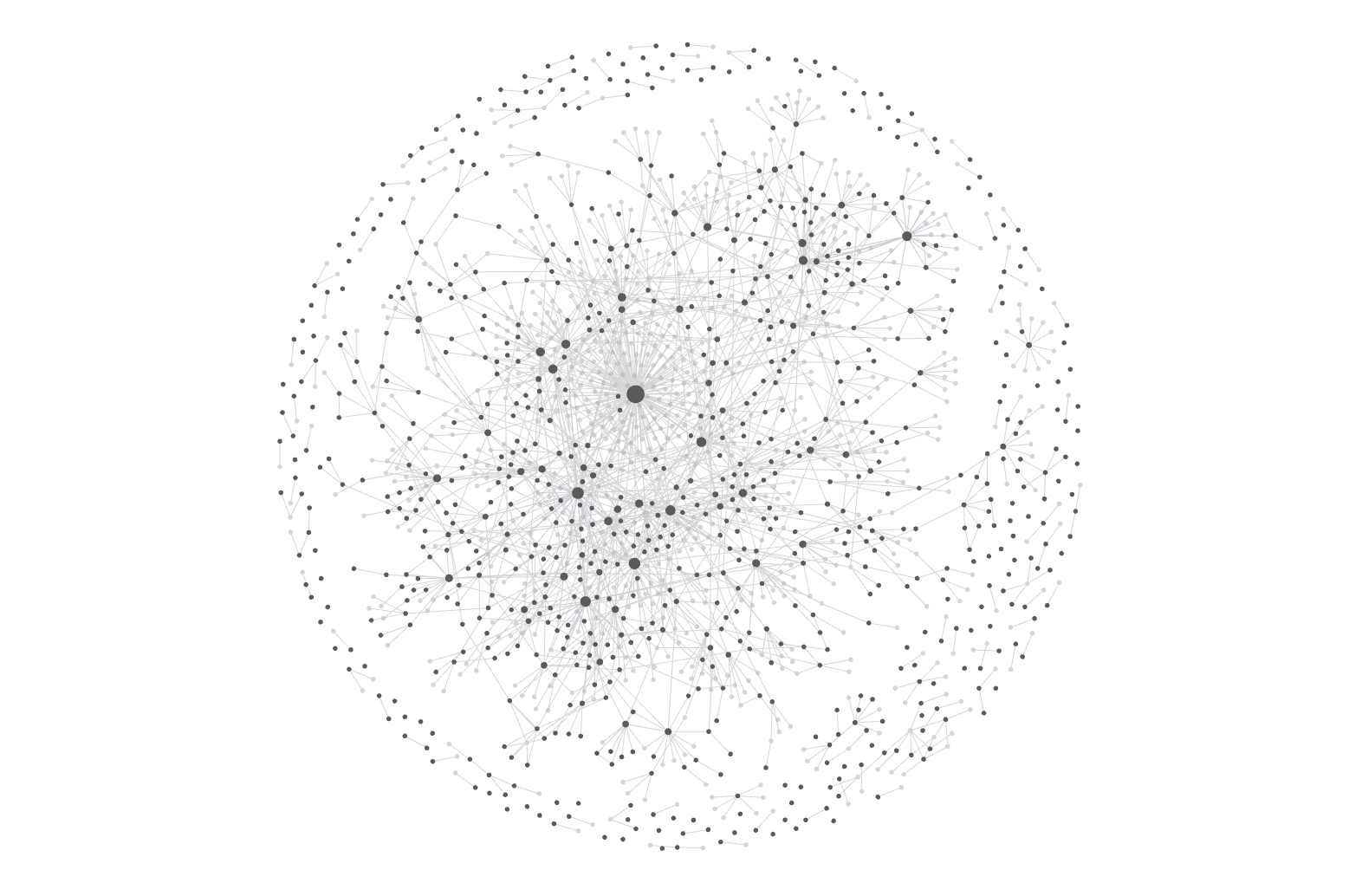

Here’s what my Obsidian vault looks like when visualised as a graph: Each dot (node) is a note. Lines indicate direct references

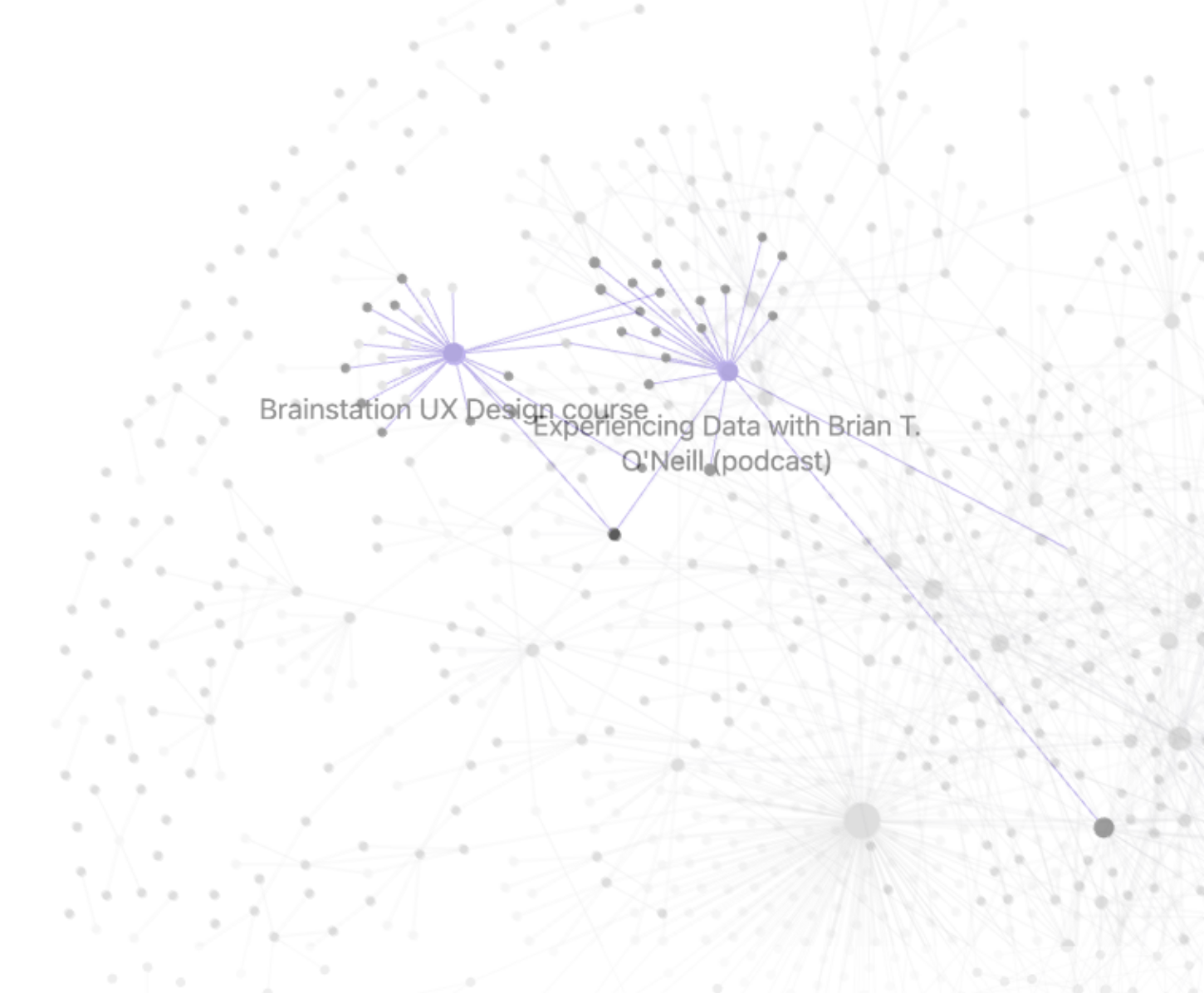

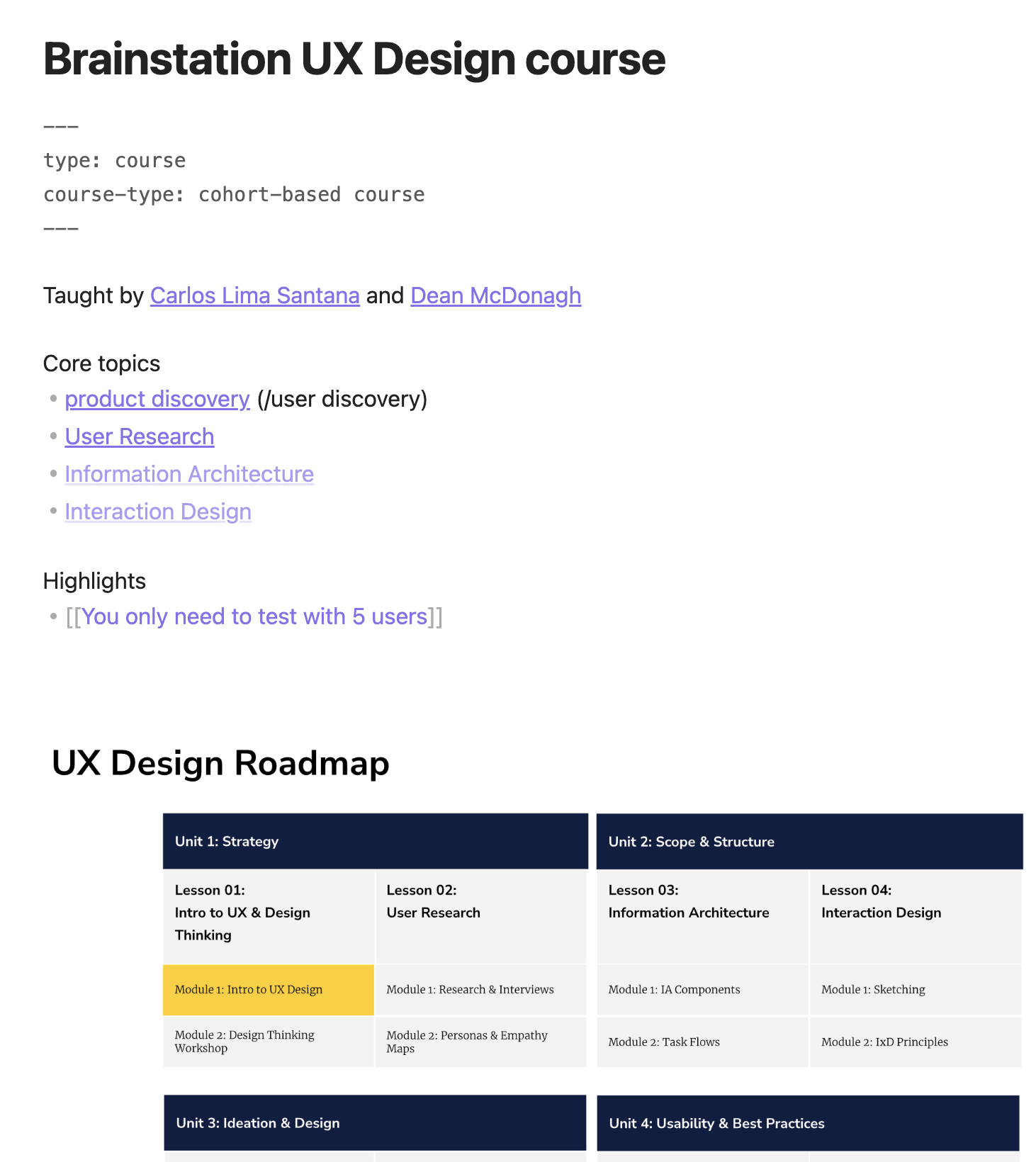

Here’s a more specific example: I have made a note about the UX Design course I recently started. As the course progresses, I am either linking this main, raw note with my class notes to existing notes (e.g. I already had one for Design Thinking), and also create new ones that are about specific concepts we covered in the class (e.g. the idea that you only really need to test an idea with 5 people at a time).

In turn, the UX design course note is connected indirectly to other related notes, like my notes on Experiencing Data podcast episodes. Experiencing Data is a podcast about the intersection of Design and data science & data product development.

Anyway, showing the graphs was more of an “isn’t Obsidian neat?” detour. The point is, you can link notes to each other, and it’s really easy to do so: All you need to do is wrap a word or phrase with double square brackets, and it automatically links that word or phrase to the note with that name. If the note doesn’t exist, Obsidian still makes the link, but the highlighted text is a bit greyed out (e.g. “Information Architecture” is a note I have not yet created, whereas User Research is)

Wrapping up

I don’t have a grand conclusion really. This is a note that recaps a conversation I’ve probably had 20-30 times now, and I wanted an easier way to share it with more folks.

It’ll also be interesting to look at it a few years from now and see how my journey towards having a working “second brain” is going. Actually, I am sort of doing that today (March 2023), given I first wrote half of this note in early 2021. So far, so good!

It’s been awesome to see my notes begin to compound with time: I keep stumbling on things I learned or did or thought about in the past that help me get stuff done, keep Present Nick accountable to past Nick’s promises and resolutions, and leave gifts for Future Nick to discover.